Most animal activists give up. Here's how to avoid that.

30 Second Summary

- The movement needs more people who are “gritty” when it comes to helping animals, meaning they (1) stick to projects for longer (usually meaning years), and (2) persevere through difficulties to keep making progress.

- You always have the ability to grow and develop, and believing in your ability to improve is important. Talent counts, but “effort counts twice.” To become better, invest more effort (especially targeted deliberate practice).

- Early exploration is important for finding better options. Don’t commit to something right away just to commit; spend at least some time exploring your choices first.

- Social support is one of the most important aspects of sticking with something. If you want to be gritty, join a gritty culture. If you want to be an animal advocate, it’s much easier if you are connected to other animal advocates.

Introduction

Why do so many vegans and activists drop out of the movement, and what can we do about it?

In this article, we’re going to discuss “grit”: the combination of passion and perseverance that leads to the highest levels of success and impact. We’ll talk about what it is, why it’s important for helping animals, and how to develop more of it.

But first, why do we need to worry about how “gritty” our movement is?

For one, there’s some research that shows that most people who go vegan or vegetarian probably go back to eating animals. This one study by itself isn’t enough evidence to be conclusive, but there is other evidence that seems to point in the same direction. For example, Gallup (a well-known polling organization) finds that the percentage of vegans and vegetarians in society has stayed relatively constant in the United States for years.

It also seems that most vegans probably never get active for animals, although there’s much less research on this.

And even for those people who do get active for animals, many are only involved in advocacy for a short period of time before stopping.

Just as a personal example, there are quite a few people who I used to do animal activism with many years ago who are now no longer involved in advocacy, and some of whom are no longer vegan or vegetarian. Life has pulled them back into the mainstream, the status quo.

And this is exactly what happens to too many people in our movement.

It’s the rare person who keeps trying, keeps failing, and keeps coming back to help animals week after week, month after month, year after year. And yet, those rare people are exactly the people who we need to be developing, if we are to create the impact for animals that needs to happen.

A Momentous Flight

I thought I would share a quick personal anecdote before we get into the weeds that shows why I have a deep personal interest in grit.

Several years ago, I was on a cross-country flight and had some time to reflect on my past projects. I desperately wanted to help animals as much as I could, and I was feeling frustrated that none of my efforts had seemed to yield much yet.

Rather than planning my next advocacy project, as I often did, I instead decided to do a quick review of all of my projects to-date and ask myself why each had failed (or hadn’t lived up to my expectations). So I took out a sheet of paper, wrote down each project I had attempted over the last few years, and what had happened with each one.

What I quickly realized was that none of my efforts had failed, really—rather, I had just stopped working on them. The projects “failed” because I quit investing in them.

I hadn’t even “given up” in the typical sense of making a conscious decision to quit. Instead, I had either gotten distracted by a new project, or I had gotten busy and forgotten about the old one, or the project had hit some kind of roadblock or plateau that led to me procrastinating indefinitely.

Seeing this written down on paper was one of those lightbulb moments for me. If I wanted a future project to be more successful than anything I had done previously, I needed to get better at sticking with it and overcoming obstacles.

In short, I needed to be grittier.

Now, I’m rather glad that I stopped working on some of those previous projects; I think a lot of them were subpar and wouldn’t have done much in the long run. But some of them might have gone much further. And if the perfect project had come along, I don’t think I would have had the grit to stick with it.

It was on that flight that I decided I was going to learn more about how to commit to projects for longer, and I was going to practice this type of commitment and perseverance. Because if I was going to have the impact for animals that I wanted, I thought, then this was a key bottleneck.

That’s why I have a deep personal interest in the role of grit in my own life and how it relates to helping animals, and why I’m interested in helping other advocates become grittier advocates who think and act long-term.

Alright, let’s dive in.

Henry Spira’s First Campaign

Henry Spira with his adopted cat. Image source: Wikimedia

(Most of the following information comes from the excellent biography Ethics Into Action: Henry Spira and the Animal Rights Movement. The full biography includes much more detail and is very worth reading for anyone involved in animal advocacy.)

Henry Spira became one of the 20th century’s most influential animal advocates, but his journey into advocacy started with a campaign against a single laboratory at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City that was experimenting on cats.

After his adopted cat inspired him to take animal ethics more seriously, Henry started learning more about how we as humans treat other animals. He discovered the dark world of animal experimentation, and he began researching what kinds of experimentation were happening in New York City where he lived (including getting information from the government through freedom of information requests). His goal was to identify a winnable goal—a campaign that had the highest likelihood of winning.

After sifting through information, he chose his target: a lab doing strange, terrifying, useless experiments on the sex lives of cats, right in the heart of New York City, just a few blocks away from where Henry lived.

He began by trying to use private channels to shut down the lab’s experiments, first by mailing the museum, but no reply came. Next, he tried going to the New York Times to see if they would cover the story of this lab’s horrible experiments; no luck there, either.

This initial research and outreach happened in Henry’s spare time over the course of a year or so. He was working full-time as an English teacher at a high school and using his evenings and weekends to push the project forward; and remember, this was in a time without computers.

At this point—if we had made it this far—many of us might have given up from the initial rejections. “The museum won’t answer me,” we might say, “and I can’t get the press to cover it. Maybe I should work on something else.” Maybe something shinier would come our way, and we would get distracted.

For Henry, though, this was only the beginning.

Henry Spira with protesters at the American Museum of Natural History. Image source: Ethics Into Action book, photo by Dan Brinzac.

In July of 1976, after laying the groundwork for a public campaign, Henry held the first protest against the museum. He had been communicating with other animal rights organizations and various radio stations, building a coalition of support so that he had collaborators and allies when the protests started.

Here was another opportunity to give up. If the first protest didn’t do anything, and the second didn’t do anything, many of us might call it quits. Henry and his coalition partners doubled down.

They held weekly protests all through the winter of 1976–1977, and all through the spring. But while they were running protests, they were also trying to get media attention wherever they could: radio, newspapers, you name it. Henry was continuing to reach out to the museum directors, in order to persuade them to shut the lab down. He and his fellow activists sent letters to the museum’s supporters, encouraging them to write in and express their concerns with the experiments. They took out ad space in newspapers. At one point, they distributed flyers to the neighbors of the president of the museum’s Board of Trustees, letting them know what kinds of wicked experiments were going on in the museum and the fact that their neighbor could stop them.

Week after week, month after month, for over a year, Henry was single-mindedly focused on this campaign. He and his partners pushed the campaign from many angles, always trying to be strategic with every step of the process, but continuing to apply pressure.

And eventually, they won.

What Comes First Lays the Groundwork for What Comes After

Henry Spira and Congressman Ed Koch visiting the laboratories where the experiments on cats were done. Image source: Ethics Into Action book.

What exactly did Henry and his coalition win?

This was a small research lab; there were only a few dozen cats experimented on each year. Experimenting on and killing a few dozen cats is still horrific, of course, but it’s nowhere near the scale of animals used by all research labs across the United States, not to mention globally. And even those numbers are small compared to the number of animals killed for food. When looking solely at the number of animals spared from future experiments, this was a very small victory.

The victory accomplished more than this immediate impact, though. It raised awareness about animal experimentation more broadly, and generated many discussions in the public and in various levels of government. The campaign also connected Henry to many people who could prove instrumental in future campaigns. And it helped Henry and his allies develop the skills needed to successfully run future campaigns.

But perhaps most importantly, the campaign showed the world that Henry and his coalition would keep campaigning week after week after week until the target of the campaign changed their practices. This knowledge was crucial for winning future campaigns (which were sometimes won very quickly).

Here’s a quote from Henry Spira himself:

“Looking at the thing strategically, if you do a campaign like this on the Museum of Natural History, the next person you go to, you send them a letter, a phone call, a fax, they pay a lot more attention to you because [they see that] you’ve got a track record… that when you start something, you finish it, and that you’re looking to win. You’re not just looking to campaign, you’re not just looking to make a lot of noise, you’re looking to win.”

The Myth of Inevitability

Nothing about Henry’s campaign was inevitable.

He could have not done the initial research.

He could have not chosen his campaign target strategically.

He could have not sent his first letter to the museum, or not tried to get the New York Times to cover it.

He could have not reached out to local animal rights groups to build a coalition.

He could have not held the first protest.

And after protesting every week for 10 weeks, or 20 weeks, he could have chosen to give up on the 11th or 21st week.

Because during that whole process, success was not inevitable.

We usually see success from the present, looking back. And from here in the present, all of that work and all of that striving seems like it was inevitably leading to success. And perhaps we think that it felt inevitable on the inside, as well, to the activists doing the work—like they felt the success coming when it came.

But that’s not usually true.

Usually, failure just feels like failure. Work just feels like work. There often isn’t some success that you can see right over there, just off in the distance, and you know exactly when you’ll get there.

For Henry and his campaigners, they didn’t know when they would be successful. But it sure seemed that Henry wasn’t going to stop until they were, whether that took 10 weeks or 100.

Our Addiction to Quickness

These days, it might be harder for us to stay focused on a single project or campaign for a long time because of how fast everything else seems to move.

Our social media content comes to us chunked in 7 second clips. Advertisements flick from screen to screen to screen. The news always updates. We can order something online tonight, from the comfort of our sofa, and have it delivered in a day or two. It seems like there’s always a new up-and-coming musician, or actor, or writer, or company.

How can we commit to one project for a whole year when things seem to move so fast?

Except, a lot of change actually happens really slowly, and the change that we see happening all around us is the result of the combined efforts of billions of people working every day on their own pieces of things.

That social media content that you consume so quickly might have taken hours, days, or weeks to produce. The company that just got so popular “out of nowhere” has probably been building its product and user base for years. The book that shoots to the top of the bestseller list probably took years to write and publish, and years of training and writing before that to hone those skills. Many efforts (such as movies, companies, products, campaigns) involve large teams of people working together for weeks, months, or years.

Henry Spira’s first campaign took over a year of his life—a year of research, writing, organizing, conversations, protesting, working—and a coalition of dedicated organizations working with him.

We have the privilege of sitting here in the present, knowing that Henry won, and it feels like a quick little news blurb: “animal rights activists successfully shut down lab experimenting on cats”. But that blurb took over a year to make happen.

Even when the news comes quickly, the change is usually slow.

If we want to have an impact for animals, we should ask ourselves: am I the type of person who is able to stick with a project long enough to see it through to success?

Or do I give up after 10%, 50%, 80%?

Effort Counts Twice

Which leads us to our main concept: “grit”.

Although the idea of perseverance has been around for forever, the specific term and definition of “grit” that we’ll be using was popularized by the author and researcher Angela Duckworth in her 2016 book Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance.

Cover of the book Grit, by Angela Duckworth. Image source: Amazon.com book listing.

When Duckworth analyzed many different situations to see what the predictors of long-term success were, she discovered that talent played a significant role—as we all would expect—but that effort and perseverance seemed to count even more than talent. “Effort counts twice” is how she puts it, with her specific equations for success:

Talent x Effort = Skill

Skill x Effort = Achievement

Thus, (Talent x Effort) x Effort = Achievement

Talent counts; but effort counts twice. And to keep applying effort in the long-run towards the same goal is what it means to be gritty.

Grit = Passion + Perseverance

Angela Duckworth defines grit as the combination of passion plus perseverance.

By “passion,” though, she doesn’t mean the quick, hot and steamy kind of emotional rush that you might get and lose in a few hours or days. Her definition of passion is more about a deep, long-lasting commitment to a certain area or goal, where the goal provides a profound sense of purpose to your life.

“Perseverance” in this context means consistently working hard and overcoming obstacles, despite difficulties and setbacks.

Put together, being gritty means (1) sticking with the same goal for a long period of time and (2) consistently making progress by working through or around challenges.

If you’re interested in how gritty you are currently, there’s a “grit score” test you can take online that takes a couple of minutes to complete. Your grit score can help you predict how much you will accomplish, regardless of the area that you’re working on.

And the good news is that grit can be trained and improved, no matter how gritty you are right now. How to improve your grit is something we’ll cover later on.

Let’s return to Henry Spira for a moment.

For many of us, campaign #1 might also be the last campaign we ever do. “Wow, that took a lot of work,” we might think. And then we might get distracted by other project ideas, or we might get pulled into the various hobbies and activities of our friends and family members. But for Henry, this was the beginning of a twenty-year dedication to animal rights that would last until he died.

Over the course of these twenty years, he and his coalition partners influenced the fashion industry, the USDA, and McDonald’s, making incremental changes to either phase out animal exploitation in some instances or at least help reduce animal suffering in the cases where ending it wasn’t (yet) feasible.

His first campaign was arguably the least impactful out of all of his future work; but the future work would have never happened had he stopped after the first project was over.

When Too Much Grit is a Bad Thing

But we don’t want to just be gritty for its own sake, of course. We’re trying to help animals. We have specific goals and outcomes in mind that we want to accomplish as quickly and thoroughly as possible.

So it’s worth looking at when grit is not helpful, before we talk about how to increase it.

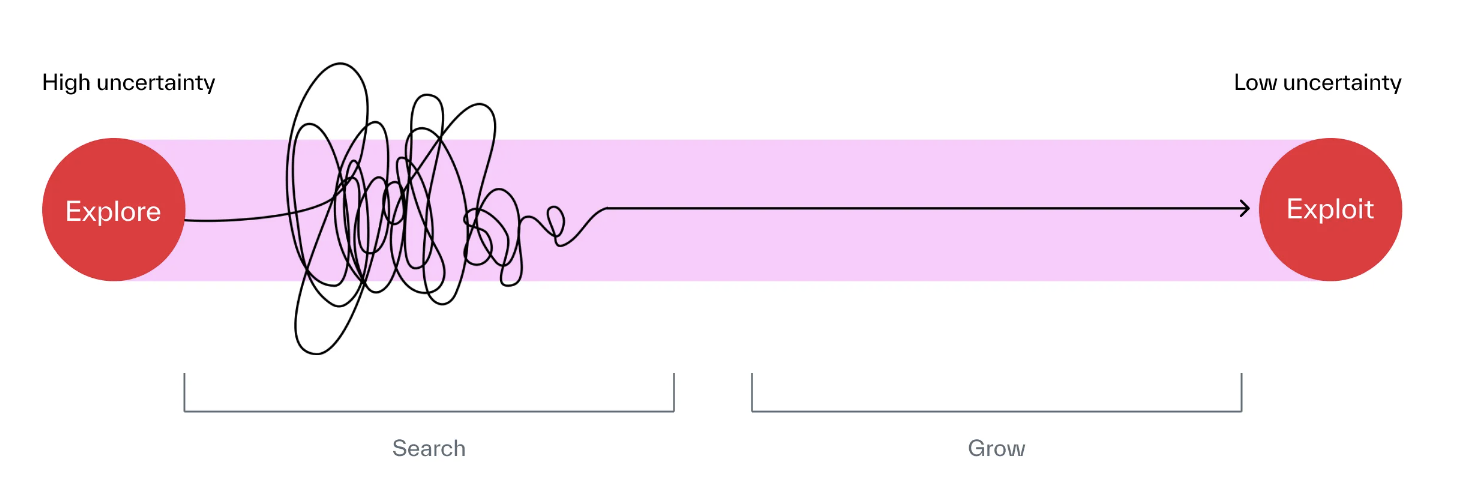

In his book Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, the author David Epstein acknowledges the value of grit but warns us against applying it before we have a clear understanding of our long-term goals and priorities.

If you’re not sure about the path that you’re on, then maybe don’t commit to it for life.

This is especially true early in your career or early in a project. In the early phases, exploration of your options has more greater value than early committing. This is because when you have lots of time left in front of you, it’s worth spending more time up front to identify better opportunities. If you’re going to be working on a project for the next two years, it’s probably worth a few weeks up front exploring all of your options before committing to one (maybe even a few months).

Likewise, if you pick a path that ends up really not working out, sometimes it’s the right thing to do to quit and change trajectories—Epstein calls this “strategic quitting,” and it could help you get onto a better path faster in the right situations.

Your grit should increase with your confidence in the goodness of the path that you’re on, compared to your other options. Or if not confidence—the world is a very uncertain place, after all—then you should at least have explored a number of options first, compared your choices, and then made an intelligent decision about which path to take.

Image showing the value of exploring first, then committing to options. Image source: Strategyzer

(For the nerdy folks out there like me who want to learn more about when to explore and when to commit, you can check out the concept of the “exploration-exploitation dilemma”, or the book Algorithms To Live By for more detailed dives into these questions.)

Epstein also discusses how valuable it can be to have a broad range of experiences and skills. Many of the toughest problems we face in the world today lie at the intersection of several different disciplines. Broadening your experiences can lead you to being more capable in the future at solving these kinds of difficult, complex, interdisciplinary problems—problems that might not be solvable by specialists with limited skills and knowledge.

How to Become Grittier, For Animals

Alright, enough about why grit is important and why we also need learning and strategy to complement our grit. In this section, we’ll talk about strategies for increasing your grit: becoming someone who sticks to things longer and perseveres through adversity.

Know You Can Improve: Growth Mindset

The first step to becoming grittier is to believe that you can. This is called “growth mindset”, discussed by the researcher Carol Dweck in her book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success.

Dweck makes the case that there are two general mindsets we can adopt: growth mindset and fixed mindset.

Someone with a fixed mindset believes that ability is innate, and people are essentially unchangeable. They will say things like “oh I’m not good at this,” or “wow they’re talented,” or other statements that indicate that some people are smart and talented and some people aren’t, and that someone’s level of talent and intelligence can’t really be changed.

Someone with a growth mindset, on the other hand, believes that people can learn and grow and develop in big ways, and that effort is crucial for progress. They will say things like “I need to work harder to improve at this,” or “I practiced a lot and that’s why I did so well here,” or other statements that indicate that effort is the key driver of improvement and success.

Of course, people are born with different genes, different brains, and different bodies, and that leads to different levels of talent and ability in various domains. These differences exist.

But researchers like Carol Dweck and Angela Duckworth have helped to show that in the long run, effort typically counts for much more than innate ability, and people do have the ability to change drastically. (Remember, “effort counts twice.”)

Sure, some people may be more talented than you, more privileged than you in all kinds of ways; that’s just life. But if you put in the effort, that effort can make up for the talent gap and then some.

Perhaps you don’t know how to write a legal brief, or how to run a campaign, or to get a pro-animal bill passed—but with enough learning, practice, and effort, you could learn to do any of those things.

Believing that you have the power to learn and grow is crucial. Focus on your efforts, rather than a false belief that your current abilities are fixed and immutable, and you will be more successful in time.

So to be grittier, you must first believe in your ability to grow and improve.

Cultivate Your Passion: Explore, Then Commit

Grit is most powerful when aimed at something you find deeply meaningful and interesting. In order to find that meaningful, interesting thing, you need to experiment with different activities, reflect on how they went, and over time learn to tie those activities to a greater purpose (like helping animals).

Exploration comes towards the beginning of this process.

Before committing to a long career in any one profession, for example, it’s probably best that you sample a lot of different fields first and see if any of them are a significantly better fit for you than the others.

Maybe you could be a perfectly fine programmer, but being a lawyer would actually be a much better match for your abilities, interests, and goals. If that’s the case, then hopefully you would discover this early in the process so that you could more fully commit yourself to legal studies.

The same logic is true with different types of animal advocacy.

There are a ton of ways to help animals. Don’t get too stuck in the first type of advocacy you come across; it might not be the most impactful, the most interesting, or the best fit for your skills and interests. Explore a little; discover all of the different types of advocacy that are out there (or at least some of them), and then you’ll be able to make a more informed decision about where to allocate your time and energy.

The exploration doesn’t have to be exhaustive; and actually, it can’t be fully comprehensive because there are too many options for your limited time. But take at least a little time to explore before committing for a longer period of time. Explore enough that by the time you hunker down on a problem, you know it’s a good one that is both important and that matches your talents and interests.

Once you’re starting to commit to a direction, reflect on that direction and make sure you can tie it into a bigger purpose. With animal advocacy, this should be fairly easy; we’re doing this to help others, to help countless beings who suffer and die needlessly. Our purpose is baked into our movement. But still, reflect on the fact that you’re committing to a path because of a deep purpose. This will make you grittier and more resilient when difficulties arise.

Practice Better: Focused Practice on Your Weaknesses

Time spent doing something casually is not the same as time spent practicing something with a focus on getting better. In particular, there’s a type of practice called “deliberate practice” that has been shown to be more effective at helping you make progress.

Let’s say you’re trying to learn a new animal advocacy skill, like writing op-eds about animal issues.

(FYI—“An op-ed is a feature on the editorial pages of a newspaper and expresses the opinion of an author, [and it] offers a new perspective on an issue that readers might not have considered before,” according to the Animal Legal Defense Fund’s guide to writing op-eds for animal issues.)

“Non-deliberate” practice might look like just sitting down and writing, with no regard for feedback or quality or improvement. It’s casual, it’s easy, it’s non-specific.

In contrast, deliberate practice involves the following:

Set a challenging goal focused on a specific skill you want to improve. In our example, maybe you want to get better at writing engaging opening lines to your op-ed that really grab the reader.

Concentrate fully and effortfully. Fully apply yourself to the task, stretching yourself to go above and beyond your usual results. It should probably feel tough, and you may get frustrated. In our example, maybe you spend 10 minutes going through a list of 10 possible op-ed topics and writing just the first sentence for what that op-ed would discuss.

Get immediate feedback. This part is really important; you want to get some kind of immediate feedback on how you did, and what you could have done better. In the op-ed practice example, it might be most helpful to have a more experienced writer than you giving the feedback, although any informative feedback from anyone is good. If you don’t have anyone to give you feedback, you could compare your opening lines to the opening lines of op-eds in popular publications.

Repeat! Repeat the task again, applying the feedback that you received.

While many types of practice will help you improve your skills, this type of deliberate practice seems to be particularly good at helping you develop faster and better. 1 hour of effortful, targeted practice like this will help you improve much more than 1 effort of casual, non-targeted activity.

And you can practice sticking to projects for longer periods of time, too, while implementing deliberate practice. The next time you choose a project to commit to, think about making a choice to stick with it longer than your previous efforts. Choose to commit for a fixed period of time, say 6 months or 1 year, and to not give up when difficulties arise during that time.

Don’t Dig a Hole With a Spoon

Sometimes, we can trick ourselves into thinking we’re being smart and gritty, when we’re actually stubbornly working in the wrong direction.

For example, you probably shouldn’t try to be super gritty at digging a hole with a spoon.

In fact, you probably shouldn’t be using a spoon at all. There are better tools available, like shovels, bulldozers, contractors who are good at digging holes… It’d be worthwhile to ask around first, do some research, and then quickly realize there are much better tools than a spoon.

And before doing that, you really want to know why you’re digging the hole in the first place. Think, research, and strategize at least a bit. What else could you be doing with your time? What is the impact of digging this hole going to be?

And if a hole doesn’t need to be dug, then don’t dig a hole.

But, if digging the hole really is the best project you’ve found to make an impact, and you’re being smart about doing at least a little thinking and research beforehand, then being gritty will help you get it done.

This is partially why continuous learning and upskilling is important. We want to be gritty when it counts, but we also need to learn what the best practices are and the best tools of the trade. Because if we’re using approaches, strategies, and technologies that are too outdated, then our persistence isn’t going to make up for that; we’re still going to fall behind.

It’s also why we need to be strategic. If we truly want to make a large difference for animals, then we need to make sure we’re working on something that has a reasonable shot at creating that impact.

Swimming laps in the pool every day isn’t the best strategy to become a better baseball player; you need to play ball.

Similarly, you need to be choosing your advocacy strategically so that your grittiness gets translated into animal impact.

Otherwise, you might find yourself metaphorically digging a hole.

(Sometimes, even small tweaks to existing activism can lead to significantly more impact. If you’re having conversations with people at We The Free events about veganism and animal rights, you could record those conversations and post them online. That same conversation can now reach dozens, hundreds, or thousands of people, whereas before it would have only reached one.)

Build Your Support Network: Why Social Support Matters

Finally, a key part of grit has to do with who you surround yourself with, and what teams and cultures you’re a part of.

In her book Grit, Angela Duckworth says: “If you want to be grittier, find a gritty culture, and join it.”

Angela Duckworth quote about joining a gritty culture. Created using Canva.

Often, we just do what our friends, family, or colleagues do. This is why it’s so important to have other pro-animal people in your life, to give you that social support to stick with it over time. Without that support, most people just drift back to the status quo.

For example, let’s say you want to learn more about different ways to advocate for animals, such as by completing the 6-week Animal Justice Academy online curriculum. Additionally, let’s say you have two options for how to complete it:

You complete it on your own.

You join a group of 5 other people who meet weekly every Tuesday evening for two hours to watch videos and discuss the course.

Which one would result in a higher likelihood of you successfully completing the course?

If you’re like most people, the group learning environment will probably boost the chances that you actually complete the course. When we are part of a group, and that group has certain norms and expectations, we are likely to keep going and follow through with those expectations.

If you’re completing the course by yourself, then other commitments or opportunities may pop up and occupy your focus. Other people might try to pull you into things, and you’re more likely to give into social pressure without having a group of people who you’re accountable to.

Humans are very social creatures, and we’re wired for conformity with our group—if our family or our community does X, we are very likely to also do X. Most of us feel social pressures quite strongly, and those pressures push us towards one action or another.

A social network showing a green dot (representing a vegan) surrounded by red dots (representing nonvegans). Image source: Connect For Animals, Steven Rouk presentation about social influence in animal advocacy.

The book Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape Our Lives goes in-depth about how powerfully the behaviors of our social connections influence us—and not only the behaviors of our friends, but even our friends’ friends.

There’s another quote from the book Grit where Duckworth quotes the researcher Dan Chambliss: “It seems to me that there's a hard way to get grit, and an easy way. The hard way is to do it by yourself. The easy way is to use conformity, the basic human drive to fit in, because if you're around a lot of people who are gritty, you're going to act grittier.”

If you want to be the type of person who does X (whatever X is), the easy route is to go join a group where everyone is doing X.

So the final piece of grit, and perhaps the most important, is building a support network of people who are engaged in the activities that you want to persist with, or people who can support you in those activities even if they don’t personally do them.

If you want to advocate for animals, join a group of people who advocate for animals. Surround yourself with people who advocate for animals. Join an advocacy-oriented community.

One way to begin that process is to attend relevant events. For example, on the platform Connect For Animals you can find lots of pro-animal events (both virtual and in-person), as well as larger conferences that pull together animal advocates from around the world, like the Animal & Vegan Advocacy Summit. These events and conferences are great places to meet people who can form part of your network of social support.

For some people, you might not need social support in your advocacy at first. But chances are, you will need it at some point: after a year, or two, or three, or five. It’s often easier to get started than it is to persist year after year.

And if you don’t have that social support when you need it, you are more likely to give up, burn out, or drift away.

Joining a gritty culture of animal advocates is a way to prevent that.

Consuming Pro-Animal Content

The content you’re consuming can also sometimes act like a proxy for social support.

When you read books by animal advocates, or when you listen to animal advocacy podcasts, or when you watch pro-animal documentaries, you’re reinforcing the importance of animal advocacy in your mind. You’re keeping it fresh and keeping your brain churning on those issues, which can help you stay committed in the long run.

For example, I’m a big fan of the book The Longest Struggle: Animal Advocacy from Pythagoras to PETA by Norm Phelps. I read it a few years ago over the course of several weeks, and during that time I was constantly thinking about animal advocacy and the history of our movement. That book helped me see myself as part of a much larger movement that stretches back through time thousands of years and will stretch into the future for years to come. It deepened my commitment to this space.

Lantern Publishing & Media home page showing animal rights books. Image source: Lantern Publishing & Media

There’s also animal rights training, like the courses and videos on We The Free’s Advocacy Training page, or Animal Justice Academy’s curriculum, or other trainings that you can find through the Animal Charity Evaluators list or our list on the Connect For Animals resources page.

We The Free Advocacy Training page. Image source: We The Free

Even though books, podcasts, documentaries, YouTube channels, and other types of content are not the same type of social support as being part of a group or having personal connections, this type of content can still be extremely helpful. It’s probably important to do both.

Conclusion

Having an impact for animals takes time, commitment, and perseverance. To keep going for the long run, we need to be gritty.

Long-term commitment and perseverance in the face of obstacles help us achieve greater success, because effort counts for more than talent in the long run. (Remember the phrase, “effort counts twice.”)

To become grittier in your animal advocacy, you can do these:

Believe you can improve. (Growth mindset.)

Explore many options.

Connect your work to purpose.

Practice deliberately.

Seek learning and knowledge from others.

Build your support network.

And if we had to boil all this down to three aspirations, they might be these:

Stick to the same thing.

Persevere through adversity.

Always keep learning and striving to improve.

And if you do this, then you may also start to realize that this is a marathon, not a sprint. You may recognize the importance of taking care of yourself and not burning out, and of going slower when you need to.

Because this is how big things happen: week by week, year after year. Grittiness and impact require you to stay in the game; staying in the game means taking care of yourself.

Sometimes things change quickly, and we as advocates should ideally be ready to jump on opportunities at those special moments when big things can happen faster. But the norm is for change to take years, decades even.

And while it’s tempting to imagine that animal exploitation and suffering is a problem that can be solved in our lifetimes, the truth is that this work is a long-term, multigenerational effort. Even if we were to end animal farming tomorrow in one country, we would need to do the same in all other countries. Even once all forms of legal animal exploitation have ended, we will still need to monitor and prevent illegal activities.

And even if we did all of that, then there’s wild animal suffering and well-being to think about and address—which is an extremely tricky topic, and is one that even most animal advocates aren’t aware of (not to mention the general public).

This is a multi-generational struggle. It may be the core work of intelligent life in the universe: to help all beings live well.

So the question is not if you can find some shortcut to fix everything tomorrow. The question is, are you willing to identify something truly important and then give it your all for years?

No matter how many difficulties you come up against, no matter how long it takes—are you willing to be gritty, for the sake of animals?

Because if you are, then you might have a chance at accomplishing something truly phenomenal.

Next Steps

Here are actions you can take right now to help develop your grit for animals

Take the “grit scale” test.

Sign up for Connect For Animals to hear about animal advocacy events and resources.

Pick one thing you really want to do more of, and find a group to join where the people do that thing. Here are some examples:

Join the We The Free community to get started with street activism or online activism. (Or if you’re more interested in blog writing, doing design work, videography, SEO, or programming, there are ways for you to get involved too!)

If you want to be a writer for animals, get connected with Sentient Media or another writing-focused organization.

If you want to be a programmer or designer for animals, get connected with Vegan Hacktivists or another tech/design-focused organization.

If you want to connect with people locally, search Meetup for local veg / animal advocacy groups in your area.

Additional Resources

1. Vegan recidivism

https://faunalytics.org/a-summary-of-faunalytics-study-of-current-and-former-vegetarians-and-vegans/

2. Henry Spira

Ethics Into Action book: https://www.amazon.com/Ethics-Into-Action-Animal-Movement/dp/0847697533

https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/sc_spira_campaign/

https://findingaids.lib.iastate.edu/spcl/manuscripts/MS470.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Spira#Animal_rights_activism

3. Social influence

Connected book: https://www.amazon.com/Connected-Surprising-Networks-Friends-Everything/dp/0316036137

Change book: https://www.amazon.com/Change-How-Make-Things-Happen/dp/1529373387/

4. The book "Grit" by Angela Duckworth: https://angeladuckworth.com/grit-book/

5. The book "Mindset" by Carol Dweck: https://www.amazon.com/Mindset-Psychology-Carol-S-Dweck/dp/0345472322

6. Range book: https://davidepstein.com/range/

7. Algorithms to Live By book: https://algorithmstoliveby.com/

8. Animal Justice Academy: https://training.animaljusticeacademy.com/products/animal-justice-academy

9. Connect For Animals